Discover key challenges in UTI management

Consider the characteristics that can put your patients at risk of failing their initial treatment. Several risk factors can impact the success of urinary tract infection (UTI) management, including recurrence,

age >50 years, recent antibiotic use,

and more.1-4 Another challenge

is the

emergence of antimicrobial-resistant

pathogens in the

community setting.5,6

Discover key challenges in UTI management

Consider the characteristics that can put your patients at risk of failing their initial treatment. Several risk factors can impact the success of urinary tract infection (UTI) management, including recurrence,

age >50 years, recent antibiotic use,

and more.1-4 Another challenge

is the

emergence of antimicrobial-resistant

pathogens in the

community setting.5,6

Are your patients with UTI at risk for antibiotic resistance?

Some patients may have an increased risk

for antibiotic-resistant infections that puts them at risk of treatment failure.1-4

With E. coli resistance growing in community settings,6 it is increasingly important to review a patient's potential risk factors. When treating UTI, be sure

to consider if your patient has any of

the following:

A history of recurrent UTI1

Previous urine culture showing antibiotic resistance2,3

Recent antibiotic exposure (within the past 12 months)1-3

Chronic medical conditions4

Prior hospitalization within the past 6 months2

Age >50 years old2

Managing UTI can be further hindered in patients based on:

Antibiotic intolerance5

Renal function7

Antibiotic allergy5

Recurrent infections are a concern for the successful management of UTI

Recurrent UTIs are often associated with resistant pathogens. This could be a challenge for your patients as 30-44% of women who have a uUTI will have a recurrence.8,9

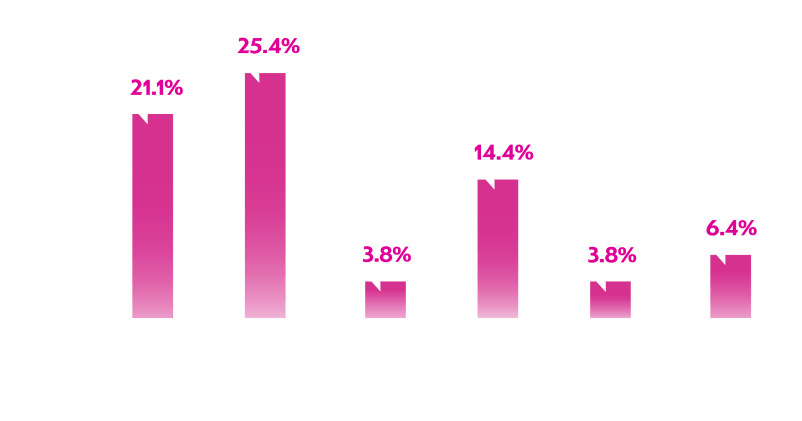

Overall rates of FQ and TMP-SMX non-susceptible E. coli were >20%*,6

Distribution of facilities in the database was similar to that of the US as a whole, suggesting appropriate demographic coverage. The prevalence of

non-susceptible phenotypes varied across geographic regions.6

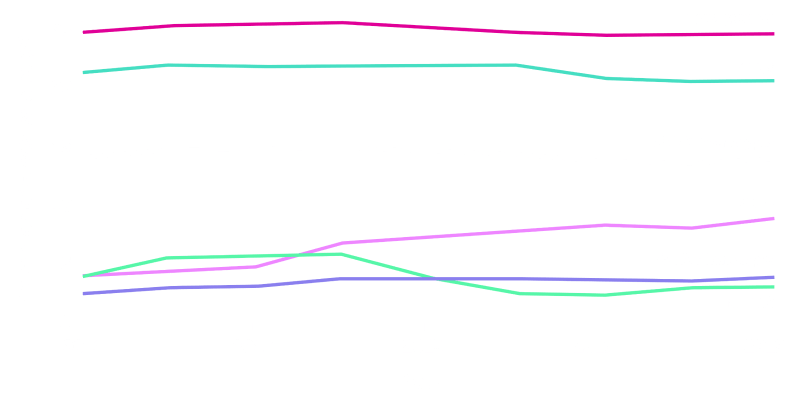

ESBL + E. coli urine isolates are growing

Data from ≥1.5 million urine E. coli isolates collected from US female outpatients*,†,6:

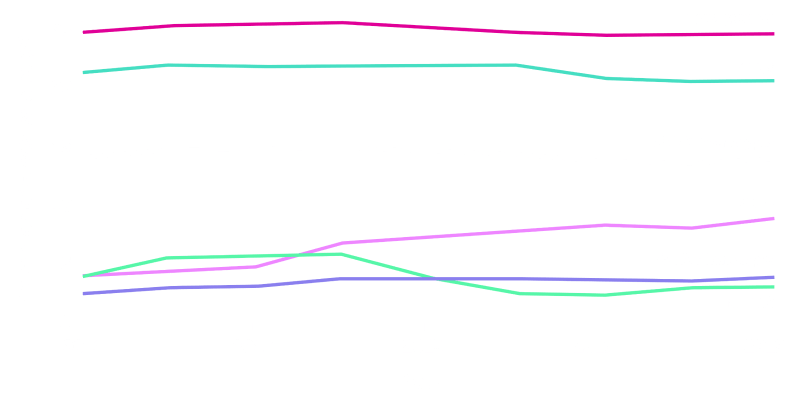

Trends in AMR Among E. coli Isolates (2011-2019)

The prevalence of non-susceptible phenotypes varied across geographic regions.

ESBL+ E. coli isolates increased an average of 7.7% (95% CI, 7.2% to 8.2%; P<0.0001) annually, rising from 4.1% to 7.3%.‡,6

‡2011-2019, except 2018.

ESBL+ E. coli can be co-resistant to TMP-SMX and FQs.10

Multidrug resistant ESBL+ E. coli can transfer their resistance genes to antibiotic-susceptible bacteria resulting in the spread of resistance to multiple antibiotic classes.11

Distribution of facilities in the database was similar to that of the US as a whole, suggesting appropriate demographic coverage. The prevalence of

non-susceptible phenotypes varied across

geographic regions.6

Data collected from a retrospective, multicenter, cohort study investigated the non-susceptibility among E. coli urine isolates collected from adolescent and adult female outpatients in the US between 2011 and 2019. Primary analysis was the prevalence and distribution of AMR. Overall, 1,513,882 non-duplicate urine E. coli isolates were included in the primary analyses. AMR among

non-duplicate E. coli was defined as non-susceptible (resistant or intermediate susceptibility results) to FQ, NFT, or TMP-SMX and also included isolates that were ESBL+. ≥2 and ≥3 non-susceptible phenotype categories defined as isolates with 2 or more and 3 or more drug-resistance phenotypes (non-susceptible to FQ, NFT, TMP-SMX, or ESBL+, respectively).6

With outpatient AMR rates rising, local patterns may be higher than you think6

Across treatments and drug classes6

US census regions saw highly contrasting estimated non-susceptible rates

(2011-2019):

| New England* |

East South Central States† |

|

| TMP-SMX | 17.1% | 29.4% |

| FQ | 10.6% | 22.8% |

| ≥2 drug classes |

7.0% | 16.7% |

FQ=fluoroquinolone; non-susceptible=resistant or intermediate susceptibility results; TMP-SMX=trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT.

AL, KY, MS, TN.

- Wesolek JL, Wu JY, Smalley CM, Wang L, Campbell MJ. Risk factors for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole-resistant Escherichia coli in ED patients with urinary tract infections. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;56:178-182.

- Trautner BW, Kaye KS, Gupta V, et al. Risk factors associated with antimicrobial resistance and adverse short-term health outcomes among adult and adolescent female outpatients with uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(12):ofac623.

- DeMarsh M, Bookstaver PB, Gordon C, et al; for the Prisma Health Antimicrobial Stewardship Support Team (PHASST). Prediction of trimethoprim/

sulfamethoxazole resistance in community-onset urinary tract infections. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;21:218-222. - Wagenlehner F, Nicolle L, Bartoletti R, et al. A global perspective on improving patient care in uncomplicated urinary tract infection: expert consensus and practical guidance. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2022;28:18-29.

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103-e120.

- Kaye KS, Gupta V, Mulgirigama A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance trends in urine Escherichia coli isolates from adult and adolescent females in the United States from 2011 to 2019: rising ESBL strains and impact on patient management. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(11):1992-1999.

- Macrobid [prescribing information]. Almatica Pharma LLC; 2020.

- Gupta K, Trautner BW. Diagnosis and management of recurrent urinary tract infections in non-pregnant women. BMJ. 2013;346:f3140.

- Foxman B. Recurring urinary tract infection: incidence and risk factors. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(3):331-333.

- Critchley IA, Cotroneo N, Pucci MJ, Mendes R. The burden of antimicrobial resistance among urinary tract isolates of Escherichia coli in the United States in 2017. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0220265.

- Reygaert WC. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018;4(3):482-501.